Most of us use operating systems everyday for playing video games, editing images and videos, writing E-mails or just browsing funny memes on r/ich_iel. But what exactly do they do and how do they work?

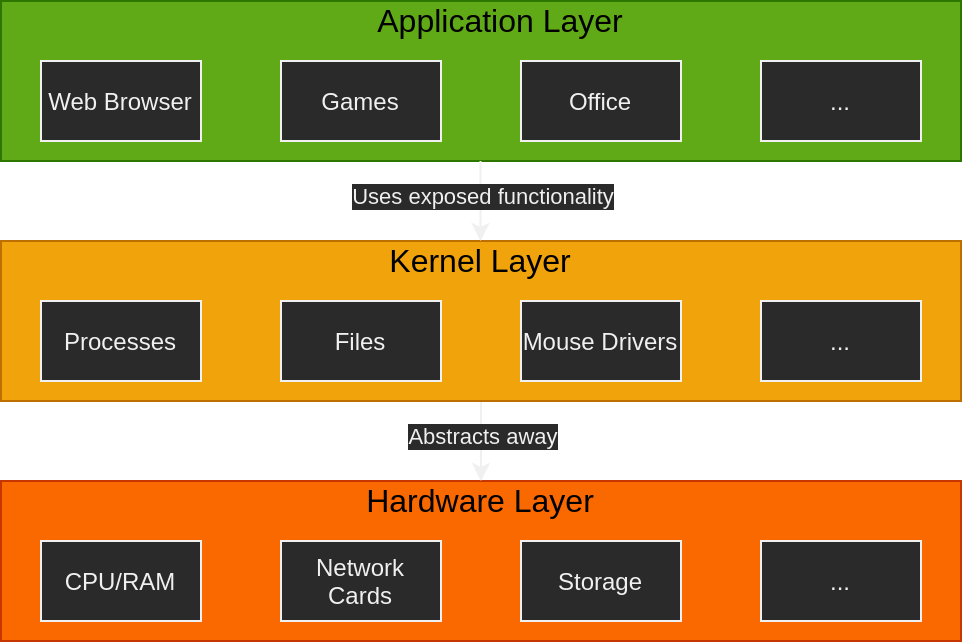

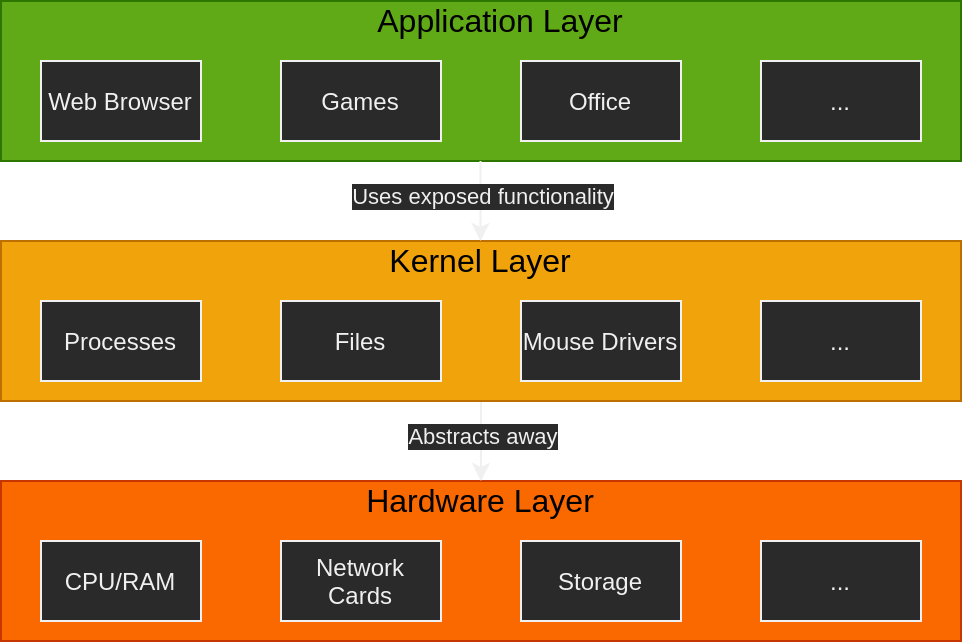

An OS known by most of us consists of two parts, the first one being the kernel and the second the applications. Applications are pretty straightforward. They are the actual programs we use and interact with, e.g. video games like League of Legends or office programs like Microsoft Word. Below those applications though lurks something else, a thing most of us never come in direct contact with: the kernel.

A kernel can be seen as the heart of any operating system. It has two main jobs which the user doesn’t need care about, but are absolutely necessary for allowing the OS to function properly, namely

The need to manage and allocate resources stems from the simple fact that system resources like computing power are limited by nature and have to be distributed efficiently among lots of competing programs. Most OSes use the concept of processes which each are allotted a certain slice of CPU time. The computer creates the illusion of multiple programs running at the same time by switching back and forth extremely quickly, usually more than once every few microseconds. The decision of how much CPU time each process gets exactly is made by the scheduler and is based on the type and requirements of the operating system.

Modern operating systems can be divided into three major categories, although there are many more:

Time-Sharing/Multitasking OSes are the ones we typically use. They usually run multiple programs a user can interact with. The scheduler tries to maximize responsiveness by giving more CPU time to processes currenly being used by the user like video games or spreadsheet calculations. Windows 10 and GNU/Linux are multitasking operating systems.

Batch operating systems don’t directly interact with the user. Rather, an operator prepares a batch of jobs to be done and shoves them into the computer. The computer then processes them non-stop and sequentially.

Real-Time OSes are often used when processing data streams. They have fixed time constraints the scheduler has to adhere to or else the system will fail. Examples include multimedia or air traffic control systems.

Aside from the important task of allocating processing time to each program, operating systems also need to manage memory and make sure requests can be satisfied properly. This is the job of the memory allocator. There are lots of different implementation and algorithms like buddy allocation, slab allocation and many more. The memory allocator for userspace programs is usually implemented in userspace as well. Tools for requesting memory or memory mapped IO are provided by kernel syscalls like the posix [mmap]. When running out of memory, the kernel could for example return an invalid pointer or error code or could even swap some data from RAM to disk.

There is lots of different hardware out there, each following

different standards and having different designs. Would it make sense to

create something like Windows but only for a specific combination of

keyboards, mice, graphics/network adapters, sound cards and disk drives?

Of course not. That’s why its a kernel’s job to expose a generic

interface. Those interfaces are often exposed using system calls and can

be accessed by userspace programs using software interrupts. Linux does

this for example by offering a read and write

system call allowing a developer to read from and write to any kind of

storage medium without needing to care whether it is an NVMe, AHCI or

even network attached disk. The kernel will choose the appropriate

driver and complete the operation correctly. Linux does the same with

its input and USB subsystems, abstracting away all the different kinds

of devices and exposing a generic, easy-to-use interface. If you are

interested in what kinds of system calls are out there, you can take a

look at this x86-64

searchable Linux syscall table.

Applications are the second big part of an OS. They rely on the kernel API for functions like opening network sockets or reading from disk, although the kernel API itself is often abstracted away by libraries like libc. Application developers don’t have to care about hardware for the most part and can write portable programs quickly and concisely. Who would think about all the layers of abstraction a simple python program like

needs to traverse before the string actually ends up in memory?

We have looked at how an OS is made up from a kernel and applications and how the kernel exposes an interface to make applications portable and development easier. Although most developers don’t need this knowledge to be able to write their programs and just need to be proficient in the libraries they use, I think this is really beneficial for understanding how computers work and finally how to write better and more efficient software.